Introduction

CONVOY PQI7 was an unmitigated disaster which cost hundreds of lives and 23 of its 34 ships. And Its downfall centred not on the aggression of the enemy, but on an Admiralty blunder. When Hitler invaded Russia In June 1941 he presented the Allies an unlikely friend in Stalin, but also a problem in how to help his beleaguered country. Supplies were In desperate shortage and there was only one route the sea.

Convoys took between 10 and 15 days to reach the Soviet arctic ports, the route being flanked by German-occupied Norway. Pack ice in the winter forced convoys closer to this treacherous coastline, but with the sole consolation of darkness for cover.

Summer months

In summer months, the route was wider, but was exposed by permanent daylight. On August 21, 1941, the first convoy sailed from Iceland to Archangel and completed its 10-day journey without incident. This was a political gesture as much as an experiment and the Allies soon pressed on with the PQ series of convoys to Russia. By February 1942, 93 ships had completed their mission with only one loss to a U-boat. But as daylight drew on in spring, the Germans upped their work rate, greatly aided by the arrival of their new battleship Tirpitz and accompanying destroyers. It took three weeks for the enemy to make much of an impact, with PQ13 losing five ships. Mixed weather reduced any certainty of enemy contact, but 16 of PQI4's 24 ships had to return to port because of pack ice and the homeward bound QP1O lost two ships to the very effective Junkers JU 88 torpedo bomber. More than 30 U-boats and 250 Luftwaffe aircraft now patrolled the area. The Tirpitz and all remaining destroyers were moved north to await convoys. The Germans were preparing to score a coup. At the end of June, PQ17 sailed. By early July, eight U-boats were tracking the convoy, as was the Luftwaffe.

Attack

On July 4 the attack developed. The Admiralty blundered and ordered the convoy to scatter. This was the beginning of the end for PQ17. In his book, Convoy is to Scatter, the late Captain (then Commander) Jack Broome - for a brief spell Captain (D) at Liverpool and the senior officer of PQ17's close escort, declared that this was "the first convoy in the whole of our naval history ever to have been scattered by anyone other than the man on the spot." The signal was executed in the mistaken belief that the Tirpitz, then the most powerful battleship, and other German surface warships, were about to attack, the convoy. The feelings of the convoy skippers and crews left to fend for themselves as they watched their escort withdraw, can be imagined. Broom was naturally bitter. He wrote:

"The First Sea Lord, our supreme Admiral, with his own pick of the whole Royal Navy as his staff never, ever, knew where, those Big Boys were when he scattered PQ17 to the wolves. - To cap it all, pathetic distress signals were already limping in from helpless merchant ships being murdered by enemy planes and U-boats."

Within an hour from the time of the fateful signal, the convoy was spread out on a 35-mile front, heading in all directions but West. The small escort group comprised corvettes, trawlers and minesweepers, skippered by RNR and RNVR officers and mainly crewed by HO (hostilities only) ratings.

Thanks to their initiative, and virtually ignoring the Admiralty's directive to proceed independently to Archangel, they sought to round up the remnants of the scattered merchant vessels, states Northern Light. "The destroyers under Captain Broome, withdrew to place themselves between the convoy and a much larger enemy who did not, as it turned out, materialise. Of the smaller war vessels, the corvette, Lotus, and the trawler, Ayreshlre, covered themselves with glory their CO's receiving the DSO."

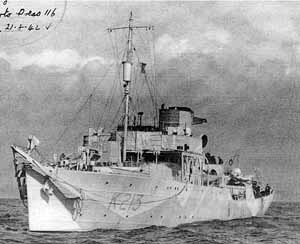

"The rest of the smaller escorts, the corvettes Poppy, La Malouine and Dianella, the trawlers Lord Austin, Lord Middleton and Northern Gem, and minesweepers Halcyon, Britomart and Salamander (by then very low on fuel), and the 13.5 knot, cumbersome banana boats, converted to ack-ack ships, Palomares and Pozarica, did the best they could for the surviving ships under very difficult circumstances."

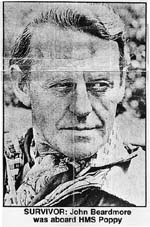

John

Beardmore, the British actor, at that time was the lieutenant navigating

officer on HM Corvette Poppy, one of the close escort under Commander

Broom. John says:

John

Beardmore, the British actor, at that time was the lieutenant navigating

officer on HM Corvette Poppy, one of the close escort under Commander

Broom. John says:

"Eleven surviving merchant ships were subsequently rescued by the remaining smaller escorts and, with their cargoes intact and 1,200 survivors from the ships that had been sunk, were shepherded into the White Sea and thence to Archangel. There, many were hospitalised and lost their frost-bitten limbs in elementary surgery. - all done without anaesthetic.

A fitting postscript to the PQ17 convoy, which, at the same time, could equally sum up the tragedy of the whole war at sea, is given by Geoff Shelton, of Shoeburyness, a member of the North Russia Club. He said:

"Never far from our thoughts were those who gave their lives in a freezing, merciless sea. They suffered the bombs, the torpedoes the mines; they suffered die straffing of machine-guns, the explosion of boilers and sea ablaze with burning oil

Some died quickly, while others, trapped in battened down hatches, held on for a few minutes, not knowing whether lack of oxygen or the cold would be the executioner. We will never know their final thoughts; we will never really know the pain of their loved ones. We, their shipmates, will never forget them. By the same thinking, we must always believe that they did not die in vain, for to believe otherwise is to nullify their sacrifice and betray them. We pray to God that he, too, will always keep them within his memory."

It was not until 12 years after the war had ended that Admiral Tovey (C-in-C Home Fleet at the time of PQ17), was allowed to publish his own dispatches in the London Gazette, telling the whole truth and apportioning the blame where it was due "not on the RN afloat, but on the Admiralty in Whitehall."

Marooned in Russia

Churchill suspended the North Russia convoys for some months after the PQ17 disaster and some of the British escort vessels and surviving merchantmen were marooned at Archangel. Crews later told of the terrible hardships experienced by the Russian civilians there and, to a lesser degree, that of the Allied crews.

Military guards were placed on all the ships’ gangways, strictly preventing intercourse with the merchant ships.

Lieutenant John Beardmore, navigating officer with the corvette Poppy

said

"although the Russian military were a tiresome lot, the civilians were most friendly towards our sailors."

In order to placate the Russians and to be in a better position to obtain food from them, the corvettes Lotus, La Malouine (flying the Free French flag) and Poppy were sent to search for a suspected Japanese raider. They did not encounter this ship but, firing a depth charge, were able to return with a supply of cod!

Our daily diet of rice and a little corned beef grew monotonous. "There were no green vegetables, apart from the odd cabbage and a few potatoes stolen at considerable risk.

The British and American survivors ashore fared even worse, continued John Beardmore. "After hospitalisation, many had been herded into compounds, and put on Russian rations." These were bare subsistence with one foodless day a week to help the Red Army.

The story of PQ17 survivors did not end there.

"Our homeward-bound convoys consisted of 15 merchant ships in ballast," adds John. "In appalling weather, six more ships including the destroyer Somali and the minesweeper Leda, were torpedoed and many of their crews drowned in the icy seas. "Of the 35 merchant ships which set out that summer of 1942, only seven got back to the UK."

Follow the link below to John Beardmore's own account of PQ17