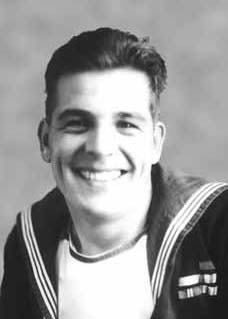

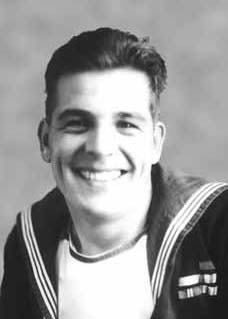

Signalman

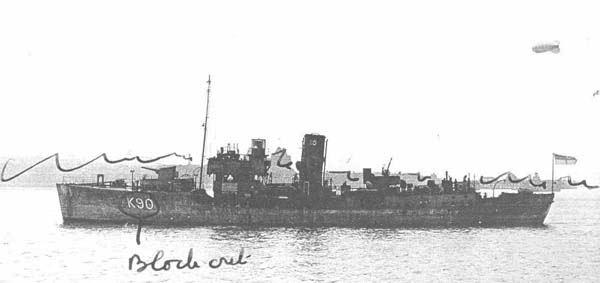

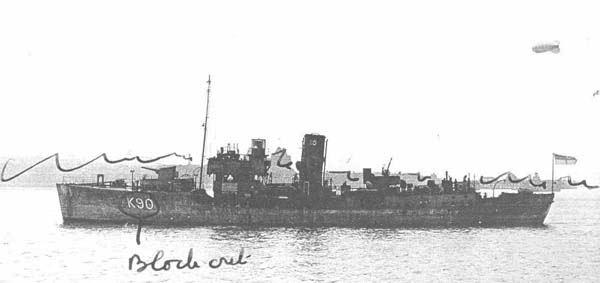

Denis Davies: Recollections of HMS Gentian Signalman

Denis Davies: Recollections of HMS Gentian

[Note: The following is courtesy of Denis' son Peter and concerns his

fathers time at sea on HMS Gentian]

The first two trips were uneventful, apart from a few submarine scares.

We arrived in Boston eight weeks after leaving Liverpool. We always seemed

to be stuck with the oldest and slowest ships in our convoys - 3 knots

flat out - and we were zigzagging all the way. Hence the reason for the

long journey.

These Corvettes were really hell ships. After three days at sea, there

was no tucker - just ships biscuits and a tin of marmalade, the ingredients

of which were very dubious. We were only allowed two cups of water per

day (perhaps) providing that the water distiller was working. The name

of the ship incidentally was "HMS Gentian". It was part of the B2 escort

group, under the control of the group leader "Hesperus", which was a destroyer

commanded by Cmdr D. McKintyre, a fearless man with a flowing red beard

and, at that time, the youngest and most decorated commander in the Royal

Navy. He was a bloody good bloke.

Our third trip proved to be the complete opposite of the preceding

two. We had hardly left the Irish coastline when the convoy came under

a heavy and sustained attack from a U-Boat pack. Ships were darting everywhere,

and confusion reigned supreme.

We, with the rest of the escorts, were busy trying to herd the merchantmen

back into their stations. We were all firing death charges like confetti,

but only managed to disturb the water. Hesperus did manage to get a U-Boat

and after that, it quietened down and we all carried on doing our business

in great waters.

Once in Newfoundland, where the Canadian Navy took over to take the

convoy into Boston we were able to relax, have a shower, haircut and a

decent feed - a whole week of heavenly bliss until the homeward-bound

convoy came in. We then took over from the Canadians, and brought them

all safely back to Liverpool. It only took six weeks, being a much faster

convoy - 10 knots - then into dock for a boiler clean, which was necessary

after each trip.

Half the crew would get a weeks leave. This was an alternative arrangement

because, after the next trip, the other half would get leave. The only

snag was that if you or I wanted to go home, you had to pay your own fare

and 10/- per week does not run to that, although we had over three months

pay, because we weren't paid at sea - just an advance at Boston. I had

to content myself with a booking in the Salvation Army or YMCA services

clubs and enjoy the pleasant hospitality that both Lime Street or Dale

Street had to offer. Also, the train service was so erratic, there was

no certainly that we would get home or get back again and it would have

taken two days travelling.

We were all ready to sail again after 9-10 days. The first night was

relatively calm; slight wind and a moderate swell. Alas those condition

lasted only until the following afternoon and then, all hell broke loose.

Not, I hasten to say through the enemy, but from the elements. I couldn't

believe it. The rapidity of the change!

Our first inkling of what was to come was a terrific lurch to port

that sent everything flying to that side, including all of us on the bridge.

We must have going almost 90 degrees because the port guns were awash.

We were all horizontal and found it difficult to get to our feet. However

after what seemed an eternity the ship righted itself and got its keel

back into the water. The wind, meanwhile, had intensified and was howling

at typhoon force. I could not keep my eyes open. Then another crash and

over we went again.

It was impossible to see the convoy or any of the other escorts; just

a solid mountain of water and pitch dark, even though it was only late

afternoon. These conditions prevailed for the next few days, then it worsened.

I was in my action station in the crows nest, and having the ride of

a lifetime. There was an empty tobacco tin up there as an ashtray and,

believe it or not, I managed to fill it with sea water as we did a heavy

roll to starboard. I swear it was over 90 degrees. I thought "This is

it. She ain't gonna come back from this!" I prepared to slide out of the

crows nest and into the water, although I did not relish the thought of

going into that raging torrent, but she, (the ship) shuddered for a while

then, oh so slowly started to come back. That was when I filled the tin.

It took what seemed ages to get back on an even keel, although it was

over in five minutes. Hell-ships they may have been, but they were really

sea worthy. The worst was still to come.

We were battered, blown and storm-tossed for a further three days then

came the big one. I was again on the starboard side of the open bridge

when we copped a beauty. It almost turned us right over. I crashed across

to the port side, smashing into the binnacle on the way and cutting my

head badly, and finished up a crumpled, bloodstained heap with the officer-of-the-watch,

and couldn't seem to function at all. Blood was all over my oilskins and

the sou-wester was full of water - only it was red. I had no tin hat on,

as we were not at action stations. A sou-wester was not designed to withstand

the impact of a brass binnacle.

At first, I thought we had been torpedoed, but I was slowly loosing

consciousness. The next thing I remember was that I was in my hammock

with my head swathed in bandages, like a Punjabi! We carried no doctor

of course and we couldn't transfer me to 'Hersperus', who did have one,

and they could not put him on board 'Gentian', so the treatment was prescribed

by signal. I recovered somewhat and, as we only had three signalman in

the crew, I felt obliged to resume duties, although I was far from well,

but the other two were keeping watches of 4 hours on and 4 off.

By this time, the poor old 'Gentian' was buggered. It was a complete

shambles. All our lifeboats and carley floats had disappeared. The lifelines

we had rigged were bobbing about somewhere in the Atlantic. The guns on

either side of the bridge had broken loose from their mounts, and were

dancing two and fro with every roll and pitch of the ship, banging against

the bulkheads. I felt sure that they were trying to get together for a

do-se-doh. However, the upshot of it all was that we were stuffed.

We had only been at sea for a month, then the captain requested, and

received, permission to go to the nearest Port because - and I quote his

signal - "We reached the prudent limit of human endurance". We made for

Ponta Delgado, in the Azores, which was a neutral port, where we were

allowed 48 hours to effect whatever repairs we could. I was taken to the

only hospital, where I was patched up a bit.

We managed to find an old cutter, which we took for our only lifeboat.

I think it was the first one ever made, and had not been painted or repaired

in that time. However, the Royal Navy, as always, had plenty of read-lead

paint and also battleship grey and, after plugging all the holes, and

18 coats of each paint, she looked sea-worthy. Thank Christ we never had

to prove it. We also managed to pinch some food (mainly onions, which

I did then, and still do hate) some bread and some fresh water, so we

lived liked kings for a day. We sailed after our time was up, and tried

to catch up the convoy. The dancing guns had been chocked and made more

or less secure, and we prayed that the weather, comprising of tempest,

tornado and typhoon, all encapsulated, had settled down a bit, which although

it wasn't good, it was certainly better than the previous four weeks.

|

Signalman

Denis Davies: Recollections of HMS Gentian

Signalman

Denis Davies: Recollections of HMS Gentian